We hope that the examination of old advertisements in

and

has shown how hard it was for Philadelphians to find a building under the old system of numbering. Below is an anonymous complaint about the difficulty of finding streets in our famous checkerboard of a grid, without the help of markers or signs. This is not an advertisement, though it is a newspaper article, and it has been transcribed for ease of reading.

Public Ledger, 25 July 1836, page 2

Marks and Numbers of Streets.—Every stranger, —psha! every resident, yes! every resident, even among those who were born and reared and raised and brought up in our right-lined, right-angled, right-looking, right-conducting city, must have experienced, at least once per day in his life, especially if he have lived long, the difficulty of telling his whereabout [sic], his bearings and distances, latitude and longitude in our streets. He may start from any given point, which he well knows when he sees it; as, for instance, Mr. Pagoda Arcade Brown’s arcade [see below]; but before he can get to the distance of five squares, he is totally on soundings and lost in the fog, and can no more tell where he is, than a sailor when out of sight of land, and the sun cannot be seen for taking an observation. We are daily accosted by elderly citizens, inquiring the way; many of them in the garb of Friends, and therefore genuine Philadelphians; people who have been born in the city, and have seldom been out of it. Not wishing to confess ignorance, we always reply that we are strangers. It goes against our grain thus to fib about the matter. But what can we do? By confessing ignorance, we must either libel ourselves or the streets, and we have too much self-respect, and too much respect for the streets, to libel either. And so we get over it by a white one now and then. Besides, we are sometimes tempted to read Jemmy MacFib’s Gotham Herald [perhaps James Gordon Bennett Sr.’s New York Herald], and “evil communications corrupt good manners.” The fact is, the streets are all alike. They are of the same length, breadth, thickness, height, complexion, appearance, aspect, look, countenance and configuration. They look as much alike as so many bed cords, spun by the same hand, upon the same wheel, of the same number of strands, out of the same lot of hemp. They have no difference, distinction, discrepancy, dissimilitude or dissimilarity. Each looks like all the rest, and all the rest look like each. They are all dressed in uniform like a volunteer company,

The streets of Gotham look like its own regiment of fantasticals; or rather like the farmer’s sons, of whom none looked alike but Benjamin. Each has its peculiarities to strike the eye, the ear, the nose or the shins. One has some half dozen magnificent churches, with steeples towering far above the city smells, into the regions of pure air. Another has no steeples at all, but is distinguished by shanties, pig styes, and slaughter houses. One is full of carts and drays, clattering like Milton’s devils in a pandemonian dispute. Another is full of omnibuses, roaring like Niagara, with the occasional scream of a woman or child, run over by the sober and orderly and well regulated drivers. The mud in one is knee deep; in another it reaches only to the ankle; while in a third, you sink over head, as in a Lybian quicksand. In one the eye is regaled by scores of dead cats; in another the nose is saluted with the odors of sundry dead dogs. In Broadway you are knocked down by an omnibus, in Pearl street by a cart, and in the Bowery by the Chicester gang. In short, no two are alike, each has its distinguishing characteristics, and you can not only tell where you are, but always perceive that you are where you ought not to be. But notwithstanding these striking, imposing, convincing differences, yet you find a guide board at every corner. So if you stumble over a dead dog in one street, and afterwards, in your course, stumble over a dead dog in another street, you have only to look up at the corner, to perceive that you are actually in another street, that you have not wandered back to your point of departure, and that the second dead dog is actually a different dead dog from the first dead dog.

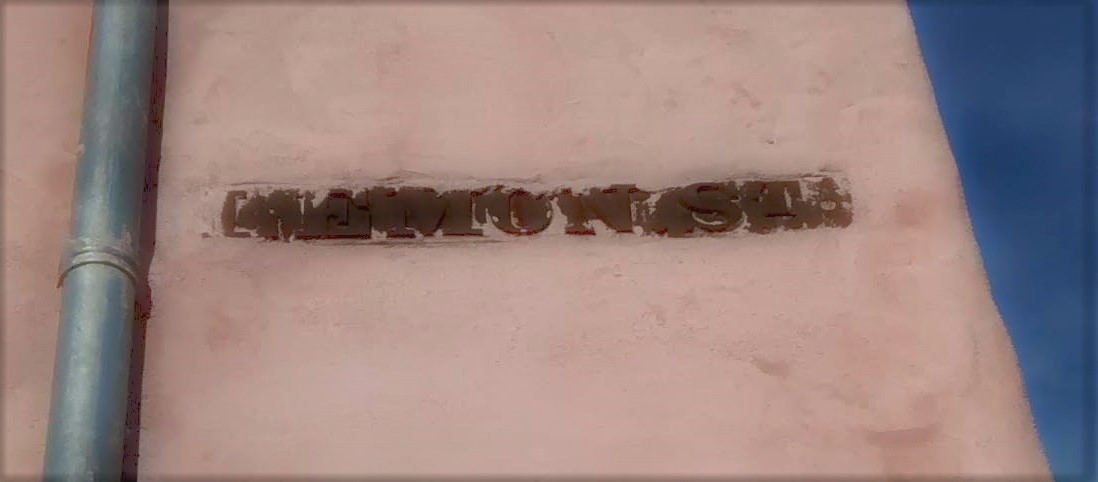

But how is it in this rectangular city, which must look to every crow that flies over it as it looks to mortals on the map, like a chequer-board or a checked shirt? In Market street you may occasionally see at a corner, something in the shape, size and color of a weather beaten shingle; and if the sun shine full upon it, you may discern a few lines of a shade slightly darker. What these marks import we know not, for we might as well decypher a charred manuscript from Pompeii in which the paper is burnt black, and the ink is—black too. Our oldest citizens tell us that according to a tradition which they received from their grandfathers, these faint lines were letters, and spelt High street.—There is a tradition that William Penn ordered guide boards to be put at each corner throughout the city, with the name of the street in fair letters, the board of one color and the letters of another. It is possible that these few brown shingles in Market street may be the remains of them. We will venture, with all due humility, to suggest to our city councils that much time might be saved, and much inconvenience and many vexatious disappointments prevented, by putting not less than two guide boards at every corner. For instance, at the intersection of High and Sixth streets, let one be on High, the other forming an angle with it on North Sixth, a third on High upon the opposite side, a fourth at an angle with it on South Sixth, and so throughout the city, at every corner. Let the boards and letters be of different colors; and we would suggest as a fact in natural philosophy, which we have read in some book, that black and white present the strongest contrast. Doctor Franklin once said of a book presented to him, that the paper and ink were too nearly of a color. The printer seems to have borrowed his notion from the old Market street guide boards.

To show the inconvenience to which strangers are subjected for want of guide boards in our verisimilitudinous streets, we would inform the councils that it cost Mr. Van Buren a walk of seven miles, to find the office of the Ledger. He walked from the Mansion House [located at 372 Market, at Eleventh, according to advertisements of 1840 and 1842] to the extremity of the Northern Liberties, and back to the extremity of Southwark, in pursuit of Chesnut street, and found a Chesnut street at every intersection. He then went up Spruce street from the Delaware to the Schuylkill, looking at each intersection for Sixth, and found they were all sixes and sevens. He knew Christ church because it had a steeple, and St. Andrew’s because it had a barn door; High street because it resembled a farm yard furnished with sheep sheds; the Arcade, because it resembled nothing in heaven above, the earth beneath, or the waters under the earth. But where to find the Arcade! At length he politely inquired if a building opposite to him were the State House [i.e., Independence Hall], and was told it was the Moyamensing Academy [likely Moyamensing Prison]. It is unpleasant for a stranger to be thus wandering about, like a turkey in the dark in pursuit of a roost.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Now about “Pagoda Arcade Brown”! Peter Arrell Browne (after whom P.A.B. Widener was named) acquired this nickname from his friends or detractors, thanks to the coincidence of his initials with the names of two extravagant and unsuccessful projects he undertook with John Haviland: the 1826-27 Philadelphia Arcade (said to be the first shopping arcade in the United States, it featured scores of shops, restaurants, and other public businesses, as well as the Peale Museum) on the north side of Chestnut between Sixth and Seventh, and an 1828 pleasure garden, dominated by a pagoda a hundred feet tall, near the Waterworks. Poe, who lived not far from the site, satirized the fondness for pagodas in his architectural writing. There was a Pagoda Street in the area long after the pagoda was lost. The pagoda itself is marked in the 1831 Simons map, and the street appears in the 1849 Sidney, 1858-60 Hexamer & Locher, 1862 Smedley, 1875 Hopkins, and 1895 Bromley maps. In the 1849 and 1862 maps, the block of Wallace that runs east-west at the northern end of Pagoda Street (which would be called North Taylor now if the block still existed) is called Arrell. Browne was a lawyer, professor, and advocate for science; for example, for the establishment of a state geological survey. He was active in the Franklin Institute, around the corner from the arcade in another Haviland building. The Academy of Natural Sciences holds his albums of presidential hair (it should be added that his studies of hair also led him to harmful racial theorizing); some of his samples were put on display during the 2016 election.

I would hate to have been a mailman in Philly in those days (or maybe mail wasn’t delivered then and had to be picked up at the P.O.).

LikeLike

Newspapers offered lists of letter arrivals, but these were probably letters for travelers. People were furious letter-writers in those days. The mail clearly went through, and perhaps with less difficulty than this ranting article suggests.

LikeLike

Although I worked in Philadelphia on and off for about a year (in the 1980s) I never really had to find my own way around so I didn’t notice whether or not that was a difficult undertaking. Los Angeles has always seemed orderly to me, despite being set on various grid patterns for the different cities… changing for Beverly Hills or Culver City or Santa Monica… depending upon streets being aligned with the ocean (the shore changing orientation from west to south) or the meandering LA River which changed direction every year or the mountains… and so on. The most difficult city I have ever visited in my travels (and I don’t claim to be a world traveler by any means) was Paris. Streets stopped after one or two “blocks” or changed direction and name. My first day out of the hotel with map in hand, intent on seeing the Seine, after a half hour of walking, I ended up in the opposite direction… just trying to retrace my footsteps back to the hotel was impossible… but I did finally make it to the river… phew! Each day it got a little easier once I had a sense of where the Seine was in relation to where I wanted to go. Anyway, thanks for another thought-provoking and memory-inducing article!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comments! So much of my time in SoCal was spent daydreaming in the back seat of the car that I have no idea how the place was laid out, except to notice that the freeway, like elevated train tracks, can destroy any sense of what is going on at street level. After living in a gridded city for many years, I get completely thrown off not only by elevated tracks but also by the presence of a diagonal street, and also find myself in the opposite direction, and without the compensation of being in Paris! As for streets set out in conformity to bodies of water, I had no idea as a Valley girl. I enjoyed the discussion of mental geography in Kevin Lynch, THE IMAGE OF THE CITY, but not the description of the “almost pathological attachment” some LA residents feel for old places like my beloved Olvera Street. If virtually the whole of a (pleasant) childhood is spent in one-story stucco buildings younger than oneself, the sight of Olvera Street cannot fail to generate a strong attachment.

LikeLiked by 1 person